Mozambique history

From Ancient Trade Routes to Liberation

Chapter 1

Origins and Early Societies

Mozambique stretches along the southeastern edge of Africa, a land defined as much by its rivers and coastline as by its people. With more than 2,400 kilometers of Indian Ocean shoreline, the country has long stood at the intersection of continental Africa and the maritime networks of the wider world. The coastline is dotted with natural harbors, coral reefs, and islands—features that would later attract Arab merchants and Portuguese sailors, but which also nurtured early fishing communities and maritime trade.

The great rivers—the Zambezi, Limpopo, Rovuma, Save, and Incomati—served as lifelines. They connected the interior highlands with the coast, acting as corridors of movement for people, goods, and ideas. Floodplains provided fertile soils for agriculture, while inland plateaus offered pastures and woodlands. The climate varied from the tropical north, rich in rainfall, to the drier south, where pastoralism complemented farming. This ecological diversity shaped settlement patterns, allowing for the rise of communities that blended farming, fishing, and herding.

Mozambique's natural resources—ivory-bearing elephants, hardwoods, gold deposits, and fertile soils—would later make it a hub for regional and international exchange. But long before outsiders sought these riches, the land itself nurtured societies whose roots ran deep into Africa's prehistory.

Aboriginal Peoples and the First Invasions

The earliest known inhabitants of southern Africa were aboriginal peoples belonging to two related but distinct groups: the Bushmen (San) and the Hottentots (Khoikhoi). At the time of Vasco da Gama's arrival on the East African coast in the late 15th century, they represented the oldest visible layer of habitation in the region.

The Bushmen, a hunting and gathering people, were masters of adaptation to harsh environments. Their languages, famous for their distinctive click sounds, embodied a rich oral tradition of stories tied to land and spirit. Small in stature but highly skilled in tracking and survival, they lived in scattered bands across the southern savannahs.

The Khoikhoi (Hottentots) appeared somewhat later in the historical sequence. Thought to have emerged from an admixture between Bushmen women and another migrating population, they were taller, organized into tribes, and herded livestock—cattle, sheep, and goats—rather than living solely from foraging. Like the Bushmen, their language retained clicks, though fewer in number. They also recognized chiefs and developed more complex social structures.

Yet both groups were gradually displaced by the arrival of new peoples: the Bantu-speaking communities who moved into the region in successive waves.

The Bantu Migrations

Beginning around two thousand years ago, Bantu-speaking peoples migrated from Central Africa, north of the Congo Basin, into southern and eastern Africa. This movement, one of the most significant demographic shifts in the continent's history, reshaped the population and culture of Mozambique.

The Bantu were physically robust and culturally dynamic. They brought with them:

-

Agriculture: cultivating sorghum, millet, bananas, and later maize.

-

Metallurgy: skills in iron-smelting and tool-making, which gave them an advantage over stone-based technologies.

-

Social organization: clan- and lineage-based systems with chiefs, councils, and ancestral traditions.

They also carried their language, defined by its characteristic noun-class prefixes: mu-ntu for "person" and ba-ntu for "people." Over generations, their linguistic diversity produced dozens of local languages, many of which survive in Mozambique today.

As the Bantu advanced, they displaced or absorbed earlier aboriginal groups, confining Bushmen and Khoikhoi to the arid southern fringes of Africa. In Mozambique itself, Bantu societies adapted to varied environments: river valleys became agricultural hubs, inland savannas supported cattle herding, and coastal zones fostered fishing communities. These societies laid the cultural and demographic foundations for Mozambique's later kingdoms.

Trade Networks and Coastal Connections

Mozambique's location on the Indian Ocean placed it at the heart of one of the world's oldest trade systems. Long before Europeans arrived, the coast was tied to Arabia, India, and even China. By the first millennium CE, monsoon winds carried Arab dhows across the ocean, bringing beads, textiles, and ceramics in exchange for ivory, gold, and slaves.

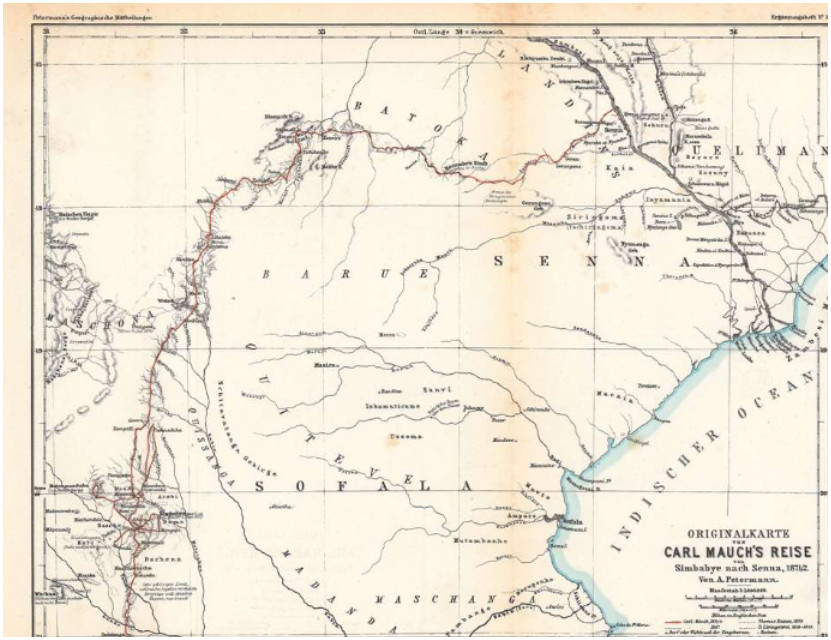

The Land of Ophir and the Zimbabwes

Legends and traditions associated the interior of southern Africa with Ophir, the biblical land of gold mentioned in connection with King Solomon. Whether mythical or real, the region between modern Mozambique and Zimbabwe was undeniably rich in gold. Archaeological evidence from the Great Zimbabwe ruins testifies to a powerful inland kingdom that thrived between the 11th and 15th centuries. Some traditions attribute the stone enclosures (the "Zimbabwes") to South Arabian prospectors as early as 2000 BCE, though most modern scholarship emphasizes African origins. Regardless, the gold extracted from this region flowed eastward through Sofala and other Mozambican ports, embedding the territory within global trade centuries before European arrival.

Islamic Coastal Settlements

From the 10th century onward, Islamic influence spread along Mozambique's shores. Arab and Swahili traders founded a chain of city-states such as Kilwa (Quiloa) and Sofala, flourishing between 930 and 1030 CE. These settlements were not colonies in the modern sense but autonomous commercial hubs that thrived on the gold trade from the hinterlands. They introduced Islam, elements of Arabic language and script, and architectural forms like coral-stone mosques.

Over time, Swahili culture emerged from the interweaving of African and Arab traditions. Coastal Mozambicans embraced Islam, intermarried with Arab merchants, and adopted Kiswahili as a lingua franca of trade. Islands such as Ilha de Moçambique later became centers of this cosmopolitan exchange, blending African roots with Indian Ocean influences.

By the time the Portuguese first sailed into these waters in the late 15th century, Mozambique was already part of a vibrant, interconnected world, shaped by both its African heartlands and centuries of external contact.

Chapter 2:

Contact and Conquest: The Genesis of Portuguese Mozambique (15th–20th Centuries)

The history of Mozambique pivoted in 1498 with the arrival of Portuguese explorers, setting in motion centuries of cultural exchange, conflict, exploitation, and resistance that fundamentally shaped the modern nation.

The Arrival: Vasco da Gama and the Strategic Coast

In 1498, the Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope and sailed northward along Africa's east coast. His arrival at ports like Sofala and Ilha de Moçambique marked a seismic shift, placing the region squarely within Europe's expanding maritime world.

It is crucial to note that Da Gama's voyage was not a first encounter with civilization. Mozambique's ports were already vibrant, cosmopolitan centers of the Swahili coast, linked by extensive trade networks to Arabia, Persia, and India. However, for the Portuguese, these harbors represented a supreme strategic prize: control of the crucial sea route to India and access to the interior's gold and ivory.

Establishing Fortresses and Ambition

The Portuguese acted quickly to secure their foothold. By the early 16th century, they established fortified trading posts (factorias) and military garrisons.

In 1505, a trading post was established at Sofala, capturing a key gold-trading port from Swahili rulers.

The Ilha de Moçambique soon eclipsed Sofala, serving as the capital of Portuguese East Africa for centuries. Stone fortresses like the impressive Fort of São Sebastião symbolized Portugal's intent to dominate trade and impose military control.

The initial Portuguese strategy was one of coastal control, not full territorial occupation. By holding key ports, they sought to insert themselves into, and ultimately monopolize, the existing Indian Ocean networks. This intrusion was immediately disruptive, forcing local rulers to constantly shift alliances and rivalries to either leverage the newcomers' power or resist their growing demands.

Indigenous Power and Internal Upheaval

Upon the establishment of Portuguese influence, the political reality of the interior was dominated by large, organized indigenous groups. Portuguese interaction with these groups was complicated by pre-existing African political structures and internal conflicts.

The Prevailing Indigenous Groups

The most powerful indigenous polity encountered by the Portuguese was that of the Mocarangas (Ma-kalanga). This extensive group's territory stretched from Inhambane up to the Zambezi River. They were distinguished by their organized political structures, ruled by powerful kingdoms. The highest chief among them held the dynastic title of Monomatapa, meaning "Lord of the Elephants," representing the powerful Mutapa Empire that controlled gold routes to the coast. The Mocarangas were noted by Portuguese observers for having comparatively "milder customs and speech" than the Muslim Swahili traders ("Moors") who inhabited the coast.

In the southern regions, specifically around Lourenço Marques and Inhambane, various agricultural groups were broadly categorized under the Tonga designation, including the Ba-Tonga and Bi-Tonga.

Major Conflicts and Demographic Shifts

The internal dynamics of the region were subject to massive, often destructive, movements that caused wide-scale mixing and scattering of established populations, a reality the Portuguese themselves had to navigate:

The Zimbos/Mazimbos Invasion: Around the middle of the 16th century, a terrifying and destructive horde known as the Zimbos (or Mazimbos) emerged from Central Africa. These warlike people were feared for their sweeping invasions that devastated the Zambezi valley, leaving a trail of destruction that dramatically mixed and dispersed the original indigenous populations of the area.

The Zulu Invasion: Centuries later, in the 19th century, the southern landscape was drastically transformed by the Zulu invasion originating from the extreme south. The Zulu's powerful military campaigns and subsequent conquests led to the creation of vast, powerful empires in the region (such as the Gaza Empire), fundamentally altering the existing social and political order of the Tonga groups.

The Interior and the Prazo System

To extend their influence beyond the coastal garrisons, Portugal utilized a distinct administrative and landholding system known as the prazo da coroa (crown lease). Beginning in the 16th and 17th centuries, the Crown leased vast tracts of land—prazos—to settlers, soldiers, or mixed-race families of Portuguese descent.

These prazos functioned like semi-autonomous feudal estates, where the leaseholders (prazeiros) exercised immense authority. Prazeiros maintained private armies (achikunda) often composed of enslaved people, collected tribute from African communities, and frequently married into local families, giving rise to powerful Afro-Portuguese dynasties.

While the prazo system allowed the Portuguese presence to permeate the Zambezi valley without direct military conquest, it was a source of constant conflict. Local populations resisted exploitation, and rival prazo families often fought one another. For centuries, Portugal's hold on the vast interior remained fragile, dependent on limited settlements and coastal garrisons rather than deep territorial control.

The Scars of Slavery and Forced Labor

From the 16th century onward, Mozambique became tragically and deeply entangled in the global slave trade. Initially, Portuguese merchants integrated into the long-standing Indian Ocean slave routes, exporting captives to Arabia, Persia, and India. However, as the demand for labor exploded in the Atlantic world, Mozambique played a growing role in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, supplying enslaved Africans to the French islands of the Indian Ocean, Brazil, and even Cuba.

The trade had a devastating impact, as raids, warfare, and the capture of men, women, and children tore apart the social fabric of communities, depopulating and weakening societies.

Persistence of Exploitation

Even after the formal abolition of the slave trade in the 19th century, exploitation persisted under new names. The colonial administration implemented brutal systems of forced labor, most notably chibalo. Under chibalo, Africans were compelled to work for minimal or no wages on plantations, in mines, and on public works like railroads. Men were often conscripted for years at a time, far from home, leaving women and children to sustain villages and deepening cycles of poverty and hardship.

This long history of slavery and forced labor not only inflicted physical and social trauma but also firmly entrenched the severe racial and economic hierarchies that would define colonial society until the moment of independence.

The Scramble for Africa and Modern Colonialism

The late 19th century brought a final, transformative phase of colonization with the Scramble for Africa. The Berlin Conference of 1884–85 compelled European powers to demonstrate "effective occupation" over claimed territories, forcing Portugal to consolidate its centuries-old coastal presence into genuine inland control, lest it lose the colony to rivals like Britain or Germany.

Portugal responded with renewed military campaigns to subdue resistant chiefs and kingdoms, transforming its tenuous hold into a more comprehensive colonial administration. This phase witnessed the final collapse of large-scale indigenous resistance, exemplified by the defeat of Ngungunhane, the powerful ruler of the Gaza Empire, in 1895. His defeat signaled that Portugal's territorial conquest, though drawn out, was nearing completion.

The early 20th century solidified Portuguese Mozambique as a classic colonial state. While the European settler population remained relatively small compared to neighboring colonies, a small white elite dominated administration, commerce, and landholding. The vast African majority was subjected to taxation, restricted movement, and minimal social investment. This inherent tension between the rulers' desire to possess and the Mozambicans' growing desire to resist would eventually fuel the powerful fires of nationalism that defined the mid-20th century.

Chapter 3:

The Weight of Colonial Rule and the Fire of Liberation

The late 19th century marked a brutal transition for Mozambique from a territory of Portuguese coastal interest to a formally colonized state. This period of intensified exploitation—driven by international pressure and economic ambition—set the stage for the rise of a powerful nationalist movement that would ultimately overthrow centuries of foreign rule.

Formal Colonization and the Scramble for Africa (Late 19th Century)

The geopolitical machinations of Europe, rather than events in Africa, triggered the transformation of Portuguese Mozambique.

The Berlin Mandate and Military Conquest

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 fundamentally reshaped Africa's destiny. Convened to regulate colonial claims, the conference required Portugal to demonstrate "effective occupation" of its claimed territories. To secure its border and prevent rivals like Britain from seizing the interior, Portugal launched aggressive military campaigns.

A defining moment came with the campaign of Joaquim Mouzinho de Albuquerque, who, in 1895, captured Gungunhana, the formidable king of the Gaza Empire, at Chaimite. This decisive action dismantled one of southern Africa's last independent states and signaled the end of large-scale African political autonomy in the region. These brutal campaigns, marked by village raze and forced relocation, successfully consolidated Portuguese authority, establishing Lourenço Marques (now Maputo) as the administrative capital.

Exploitation by Charter: The Mozambique Company

Lacking the resources to administer and develop the vast territory, Portugal delegated control over provinces like Manica and Sofala to private entities, most notably the Mozambique Company (chartered in 1891). This company acted as a colonial state-within-a-state for 50 years, ruthlessly exploiting resources such as gold, ivory, and agriculture. The company relied heavily on chibalo (forced labor) to compel Africans to work on plantations and infrastructure projects, prioritizing the profits of European shareholders over local welfare.

Indigenous Resistance and Defiant Spirits

African communities met this new, intensified colonial order with fierce resistance. The Barue Revolt of 1917, centered in the Zambezi valley, stands as a testament to this defiance. Led by the spiritual leader Nongwe-Nongwe, Barue and Chewa fighters invoked ancestral spirits and traditional rituals to rally against Portuguese labor demands and cultural suppression. Though eventually overwhelmed by Portuguese troops and superior weaponry, the uprising, along with others among the Tsonga and Makua, reflected a deep and enduring resolve to protect autonomy and cultural identity against foreign domination.

The Seeds of Nationalism

By the early 20th century, the new colonial order had solidified, characterized by land alienation, heavy taxation, and forced labor. Yet, the very system designed for control inadvertently sowed the seeds of its destruction.

The Educated Elite and Urban Centers

Colonial policy severely restricted education for Africans, limiting it mainly to missionary schools to promote assimilation. However, from the resulting small educated elite—teachers, clerks, catechists, and lower-level civil servants—emerged the first political consciousness.

Urbanization also proved crucial. Cities like Lourenço Marques and Beira became spaces of cultural and political exchange. Africans working as dockers or railway workers encountered not only Portuguese settlers but also migrants from neighboring, more politically advanced territories. They accessed newspapers, engaged in labor strikes, and absorbed the rising tide of Pan-Africanism and anti-colonial thought sweeping the continent.

Exile and the Formation of FRELIMO

The independence of Ghana in 1957, followed by other decolonization movements, provided powerful inspiration. Many Mozambican activists went into exile, primarily in Tanganyika (later Tanzania), where they connected with other liberation movements and gained political and military training.

The early nationalist organizations—such as the Mozambique African National Union (MANU) and the Mozambique African Democratic Union (UDENAMO) of the late 1950s and early 1960s—were initially fragmented by region and ethnicity. In 1962, these groups united in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, to form the Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (FRELIMO), the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique.

FRELIMO and the Liberation War (1964–1974)

Under the banner of FRELIMO, the struggle for independence escalated into a full-scale armed conflict, officially beginning on September 25, 1964, with attacks launched in Cabo Delgado Province.

Leadership and Strategy

FRELIMO's first president was Eduardo Mondlane, a U.S.-educated sociologist who articulated a unifying vision of a multi-ethnic, non-tribal Mozambique. Mondlane's assassination in 1969—widely believed to have been carried out by the Portuguese secret police—was a major setback. Leadership was successfully transitioned to Samora Machel, a former nurse and charismatic military commander who transformed FRELIMO into a disciplined guerrilla force.

FRELIMO employed classic guerrilla tactics: ambushes, sabotage of infrastructure, and, crucially, political mobilization of the rural population. In so-called "liberated zones," FRELIMO established rudimentary schools, clinics, and administrations, demonstrating the tangible benefits of self-governance and winning the support of rural communities.

Regional and Global Dimensions

The war was not fought in isolation. Tanzania, under Julius Nyerere, provided safe havens and logistical support, while the Organization of African Unity (OAU) channeled resources. The conflict was also a Cold War battleground: the Soviet Union, China, and the Eastern Bloc supplied weapons and training, while Portugal, a NATO member, received backing from some Western allies. Despite Portugal's military superiority, the long, draining conflict—fought across three African colonies—caused severe domestic discontent among Portuguese conscripts and citizens.

The Carnation Revolution and Independence (1974–1975)

The war ended abruptly due to a political event in Europe. On April 25, 1974, Portuguese army officers, weary of endless colonial wars, staged the Carnation Revolution, overthrowing the decades-old dictatorship in Lisbon. The new government immediately signaled its intention to end the colonial conflicts.

The transition in Mozambique was swift. Negotiations between FRELIMO and Portugal culminated in the Lusaka Accord of September 1974, which recognized FRELIMO as the legitimate representative of the Mozambican people. As a transitional government was formed, Portuguese settlers—many fearful of reprisals or political change—began to leave in large numbers.

On June 25, 1975, Mozambique declared its independence, with Samora Machel as its first president. The end of nearly five centuries of Portuguese rule was a historic moment, not only for Mozambique but for the final dismantling of African colonialism. Yet, the victory was only the beginning; the newly independent nation faced the immense challenges of rebuilding a shattered society, forging national unity, and navigating the fraught geopolitics of the Cold War era.

related content